DFV Prevention Month feature: How we can better understand gender-based and disability violence

May is Domestic and Family Violence (DFV) prevention month.

The theme for 2025 in Queensland is: Take positive action today to build a safer Queensland.

Through various areas of our work, we’ve been contributing to the understanding of the impacts of domestic, family and sexual violence in Queensland communities.

This includes research projects to understand experiences and responses to DFV in Queensland’s multicultural communities, and the impact of DFV on people with disability in Queensland. We helped the Queensland Government establish an integrated peak body for domestic and family violence (DFV) and to produce the Queensland coercive control communication framework.

What we know from this work is that positive action needs to include tailored responses for those who are more likely to experience DFV and sexual violence and abuse or have additional barriers to seeking and accessing help.

Prevalence, economic cost and factors driving violence against women and gender-diverse people with disability.

It’s very difficult to locate an agreed-upon figure for the count of violent deaths of women in Australia last year, but no matter what source I use, I feel a flash of anger that the numbers are this high.

Counting Dead Women Australia, a project of Australian advocacy group Destroy the Joint, recorded 78 deaths in 2024A project spearheaded by journalist Sherele Moody called Australian Femicide Watch, additionally tracks deaths of Australian women overseas, and it identified 101 deaths in 2024.

This is appalling. Within those figures, I am wondering how many of the women or gender diverse people are also disabled?

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, women with disability are more likely than women without disability to have experienced a range of violent behaviours even if it does not result in homicide.

The rate of Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence-related (FDSV) homicides of women, girls and gender diverse people with disability is unclear. The Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network (ADFVDRN) indicates this may be due to underreporting, pointing to inconsistencies in data identification and the definition of disability.

DFV is not only distressing but economically costly. A report delivered by Taylor Fry and the Centre for International Economics (CIE) for the Disability Royal Commission estimated that the economic cost of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disabilities in Australia is between $46 to 74.7 billion annually.

Why do women, girls and gender diverse people with disability experience more violence?

We know from our work specific to DFV against people with disability that there are extra risk factors, as well as additional barriers to leaving abusive relationships, particular to the circumstances of people with disability. We’ve heard from people that:

- options for leaving domestic situations can be especially limited for people with disability, for example if they are dependent on a disability support pension to cover their cost of living and/or because of lack of accessible housing options

- DFV support services, as well as related justice proceedings, are not always accessible for some people with disability

- people with disability have strong reasons to doubt if they will be listened to or believe when they disclose experiences of abuse or violence.

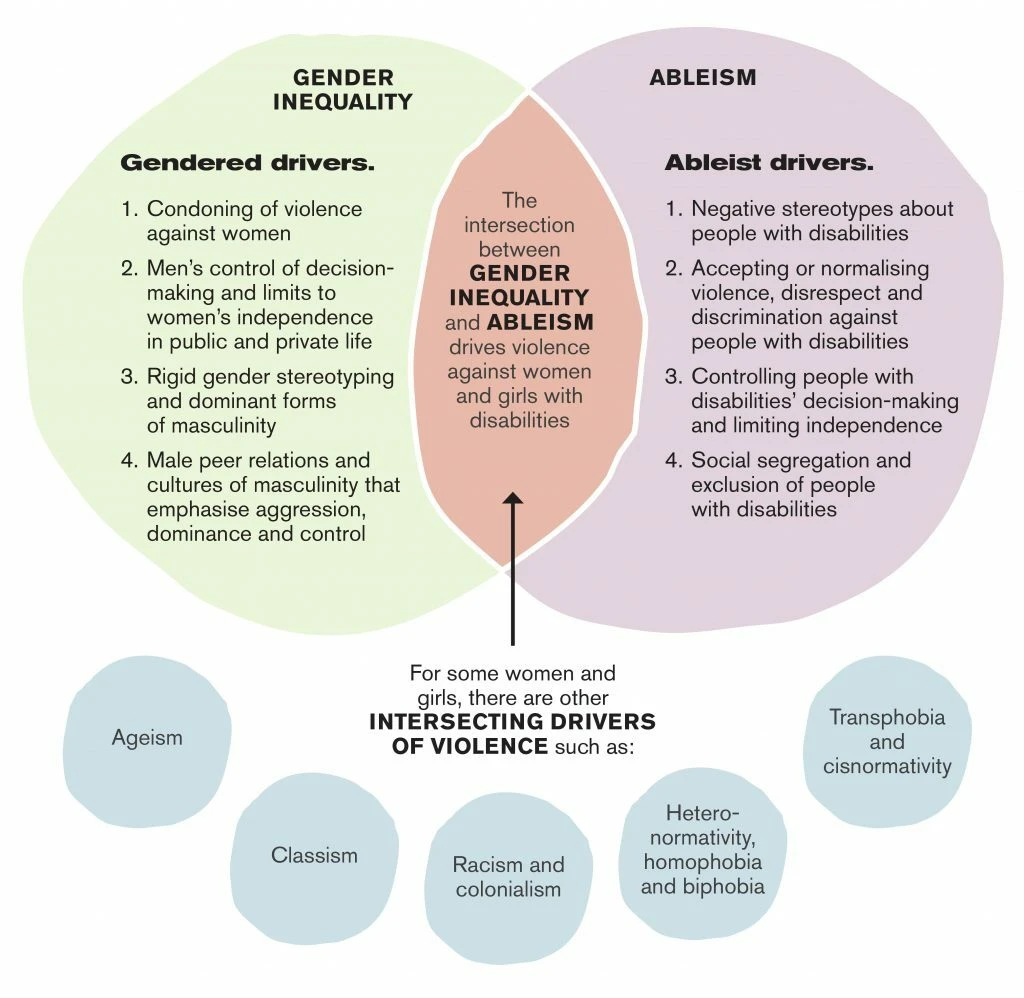

This is all intensified by intersecting disadvantage. That is, both gender bias and ableism contribute to the outcome. In Our Watch’s guide, Changing the Landscape, they describe this process:

“Specific expressions of gender inequality and ableism intersect and compound to create an environment in which violence against women and girls with disabilities is perpetrated, accepted and, in some cases, even encouraged.” p.35

The following diagram (from Our Watch and Women with Disabilities Victoria) details how gendered drivers and ableist drivers intersect to contribute to violence against women and girls with disability. For example, gender stereotypes about women being polite and subservient can be compounded by negative attitudes or assumptions that people with disability cannot be independent.

What you can do

This DFV Violence Prevention Month, I’m asking you to share the following actions we can all do to help prevent violence against women and gender diverse people with disability. Understanding how violence against women and girls with disabilities occurs is the first step in breaking the cycle.

- Listen to the voices of lived experience – seek out podcasts, books, TV shows etc. Perhaps watch or listen to something together with family and talk about it afterwards about what you learnt and share your recommendations with others – some suggestions include Adolescence (Netflix) and You Can’t Ask That (ABC)

- Learn about the warning signs of DFSV – you can learn about the signs of coercive control and unsafe relationships and find more DFSV resources for women with disability.

- Learn more about keeping yourself safe – if you are a woman with disability or supporting women with disability in your life, Women with Disabilities Australia’s Neve website has information on staying safe.

- Start a workplace conversation through training – for organisations wanting to start the conversation with their staff, Our Watch and Women with Disabilities Victoria have put together a series of explainer videos.

- Know how to respond or call out problem behaviours and attitudes when you see them – this should be something we all can do, but it’s particularly important for those who support people with disability in their homes to be confident to respond and call out problem behaviours. There are resources and tools available to help you.

This DFV Prevention Month, consider what actions you can take in your homes, workplace and community. What will you do?